As the national conversation about racism continues — and as coronavirus disproportionately harms people of color due to longstanding health disparities, jobs that can’t be done safely from home, and more — we wanted to take a moment to share with you a few of the racial disparities in Texas that affect Black children and other children of color.

We’ve pulled together a small sample of those disparities, highlighting some of the data points and graphs that we’ve published as part of our policy research over the last few years. As you’ll see, many of these disparities start very early in life.

But we don’t want to just point out the data. Researchers in both public health and communications have warned that simply pointing out disparities in a vacuum often reinforces stereotypes, as Harvard’s Dr. David R. Williams recently said on this excellent podcast discussion about health disparities. Instead, these experts call for explaining why the disparities exist, what the solutions are, and how current policies fall short for people of all backgrounds. (We tried to summarize those messaging concerns and suggestions in the last section of this blog post.)

School Disciplinary Practices — Including Suspensions in Pre-k

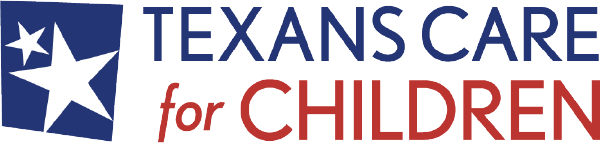

In 2017, the Texas Legislature recognized that there was a problem with school districts suspending thousands and thousands of little kids — we’re talking about students in pre-k and other early grades — rather than implementing strategies that actually improve behavior. Many districts have made improvements the last few years, but our research found that in 2017-2018, Texas districts were still 2.5 times more likely to suspend Black students in these early elementary grades compared to White students. One of the reasons: For Black students and boys, research demonstrates that early childhood teachers scrutinize their behavior more closely, even in controlled academic studies in which children behaved appropriately. Our report has several recommendations, including better monitoring of suspension data at the state and district level, including by race, and implementing proven strategies in schools to support teachers and students and improve behavior.

Racial disparities continue into the older grades, both in the over-use of ineffective school discipline techniques and the under-use of services like mental health services and support. Our previous research noted, for example, that Black and Hispanic youth are less likely than White youth to initiate or receive mental health treatment.

Impact of State Cuts to Early Childhood Intervention

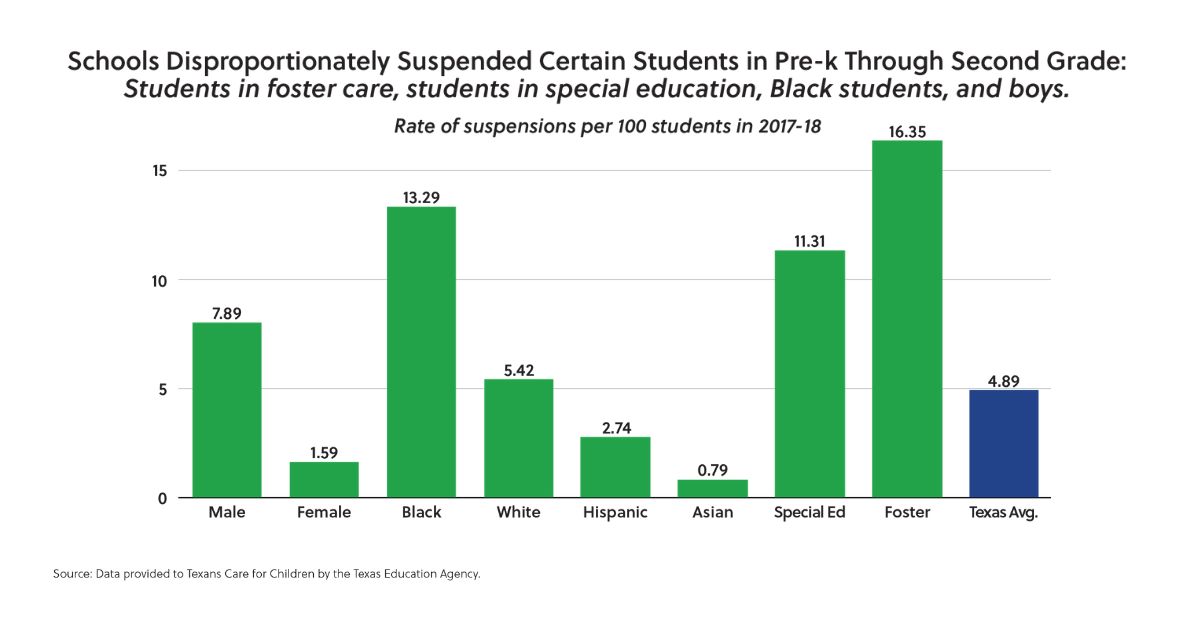

Ever since the Legislature cut funding several years ago for therapy for babies and toddlers with disabilities and delays, there’s been an uproar about so many kids — of all racial/ethnic backgrounds — losing Early Childhood Intervention (ECI) services. Unfortunately, our research found that the state cuts took a particular toll on Black kids, whose enrollment in ECI fell by 27% from 2011 to 2015, compared to a 14% decline for Hispanic kids and 11% for White kids. Kudos to HHSC for responding to our research by acknowledging the problem and working to better understand and reverse this racial disparity. We also need to get the Legislature to fully fund ECI, including Child Find outreach efforts that ensure families of color are aware of ECI and know how to access services if needed. We made progress during the last legislative session. But we have a lot more work to do, such as fully funding ECI during the upcoming legislative session and ensuring that toddlers are screened for disabilities during checkups and referred to ECI when needed.

Maternal and Infant Health

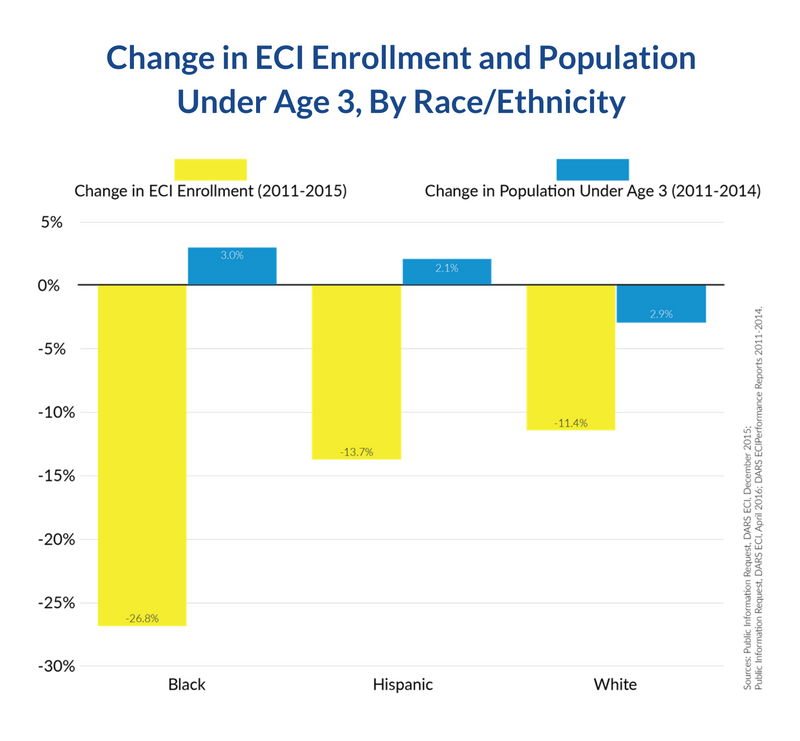

As we recently explained, Texas is one of the only states where Medicaid health insurance is typically not available to women with jobs below the poverty line, except during their pregnancy. Sadly, but not surprisingly, Texas also has disturbing rates of infant and maternal mortality, babies born too small or too early, and other pregnancy complications. Black families face particularly high risks. The state’s Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee found that Black moms in Texas were more than twice as likely to die compared to non-Hispanic White women. Infant mortality rates have decreased in Texas over the last decade, but Black infants in our state are still twice as likely to die during the first year of life compared to White and Hispanic babies. Black moms in Texas are more likely to experience maternal depression, and less likely to receive treatment, compared to other moms.

Experts have identified several factors that contribute to racial disparities in maternal and infant health: Implicit biases in our health care system can affect the quality of health care provided, decision making, and how health programs are carried out. The physical toll of ongoing stress can affect the health of mothers of all backgrounds and their pregnancies, and persistent stress related to racism adds to this “weathering effect” on Black women’s health. Social determinants of health — such as housing, food scarcity, and education, among others — are affected by past and present discrimination. Black families in Texas also have less access to health insurance compared to White families. (To learn more about these factors, read our report, IUPRA’s report, and this new report from ZERO TO THREE or listen to that podcast with Professor Williams.)

One of the ways state policymakers can reduce disparities in maternal and infant health is by expanding access to health insurance. In Texas, there’s a big gap between the uninsured rates for Black adults (23%) and White adults (15%) under age 64 — but BOTH groups, along with Hispanic Texans, have worse uninsured rates than the national average for non-elderly adults (13%). In other words, by expanding health coverage, either through postpartum coverage for new moms, Medicaid expansion, or other measures, the Legislature would take a big step towards supporting Black moms and babies while also helping Texans of all backgrounds. Reducing the growing uninsured rate should also be part of the state’s strategy to respond to coronavirus and the recession.

CPS Removals — Including the Connection to Maternal Health

We found in our research that CPS’ disproportionate removal of kids from Black families is one reason that many Texas moms are scared of asking for help for mental health and substance use when they need it. In Texas, Black children are overrepresented at every stage of CPS involvement, reflecting implicit biases among people at each of those stages, higher levels of poverty and stress, and other factors. For instance, Black children are 11% of the statewide child population and make up 21% of children removed into foster care in Texas. Statewide, Black children are 1.7 times more likely to be reported to CPS, nearly twice as likely to be investigated, and nearly twice as likely to be removed by CPS compared to White children, according to fiscal year 2018 data. State leaders should seek to keep more children safe and with their families by drawing down federal child abuse prevention funding through the Family First Act. State and local leaders should closely track and root out disparities and ensure that families of color receive the support they need to thrive.

Moving Forward

These are just a sample of the racial disparities facing Black children and families in Texas and a few examples of practical steps that state leaders and communities can take to start addressing them. It’s time for policymakers, advocates, community leaders, school districts, health professionals, and other Texans to learn more about these and other disparities, listen to the experiences and insights of Black people and other people of color, and commit to combating these disparities through systemic policy changes. By reducing and eliminating these disparities, we will improve the lives of Texas kids and create a stronger and more equitable Texas for generations to come.